The Country Gentleman, December 16, 1922, pages 1-2, 32:

What Makes the Radio Laugh?

Finding Out Exposes You to a Fell Bacillus--By John R. McMahon

THE radio bacillus began to nibble at me a few months ago. Thinking it was something else, I scratched and also used a fine-toothed comb, which did not alleviate the situation. Could it be a form of mental eczema, one of those newfangled ailments which is diagnosed by the formula "Something is biting me," and is cured by the patient's repeating to himself, "Nothing can bite me"?

"Look here," I said to my wife sternly, "everybody is doing it, but is that any reason for us to follow suit and to become dotty or loco? Quite the contrary."

"So you are really thinking about it?" she asked gently.

"Not at all! Why do you misunderstand me? Of course I can't help making a few remarks when the papers are filled up with this radio dope, programs published every day of half a dozen broadcasting stations within a radius of 500 miles, and radio shops getting as thick as grocery stores."

Fine for Robinson Crusoe

"THE air is full of messages, they say, but why should we want to hear them? I admit it would be fine for Robinson Crusoe or someone living far from town. But we are not isolated, we have a daily newspaper, and when we are hard up for gossip we can listen in on our party telephone."

"You are quite right, dear," said my better half as one who humors the patient.

"Well, I am willing to be shown. If there is any merit in this new stunt, I am for it. Traveling round the country, I have listened in a few times and haven't heard anything particularly startling or worth while. They seem to feed the air with a lot of phonograph records. I don't like canned goods close up and it doesn't improve the flavor to get them at long range. Another thing, I see all the programs make a big feature of bedtime stories. There is Uncle Piggley, The Man in the Moon and others who reel off baby talk every night to send the little ones into bye-low land. Do you think I need anything like that?"

"Not yet, darling," she replied.

"Ha, ha! That's good. Perhaps they will put on lullabies for grandpas later. But doesn't it sound funny to put an infant in his crib and then clamp a pair of ear phones on his head to narcotize him with the bedtime drool of a whiskered nurse who sits in a broadcasting station several hundred miles away?"

"Now you are talking nonsense and you know it," said my wife decisively. "I am sure every mother is grateful for the bedtime stories, and she is entitled to have help in putting the children to sleep. You know the day is coming when men will have to do more work in the home and certainly they will be glad to turn over part of their nurse's duty to the radio. As for the quality of our present bedtime stories, I don't know much about it. But just suppose Eugene Field and James Whitcomb Riley could talk to sleep every night several hundred thousand little children. Wouldn't that be wonderful and far better than anything the average mother could do for her children? Some day, if not now, there will be new Fields and Rileys entertaining American children by word of mouth."

"Say, I'd like to hear Vachel Lindsey myself over the radiophone!" I exclaimed. "Lot of other people, too, whose stuff is not much good on the printed page, but it sounds fine when they talk it. Well, I see you are trying to argue me into getting a radio set."

"No, dear," replied my wife. "Our nursery is unoccupied at present and, as you said the other day, the radio business is still in its infancy, although there are a million sets in use, and the programs will be improved in time, so we had better wait a while."

"Did I say that? Of course it is all right to wait, but there is no sense overdoing it. How do we know whether the programs haven't improved since we talked it over last? We don't want to be too darned conservative and wait until they begin talking with the people in Mars and there is such a rush to listen in that the radio factories can only supply half an earful per capita. That would be worse than the coal shortage.

"Here's another thing, we have a property right in the ether. We own the land underneath our place down to the center of the earth; we also own the air quite a ways up. We are using more or less of our land and our air, but we are letting our ether go absolutely to waste. This is not economical. Think of all the free music, lectures, sermons, market and weather reports and miscellaneous dope that is slithering daily and nightly through our home ether and our not getting a nickel's worth of good out of it. We ought to get dividends out of this ether."

"Which set are you planning to buy?" asked my spouse.

"Don't anticipate, Sophronia! That's an irritating habit. I was merely discussing the pro and con without committing myself. If I did buy a set, it would be largely for your benefit. But I may build a set; since I am naturally ingenious and all that."

A Progressive Disease

WE DROPPED in that evening at a neighbor's house and found a six-foot man of adult intelligence tinkering with a homemade radio set. He had bought about three dollars worth of raw material, which looked suitable either for an embroidery party or a horse-doctor's kit. These things had queer names, like galena, cat's whisker and tickler. I surmised that the cat's whisker tickled the galena and this made the radio laugh. An important part of the apparatus was a wire-wrapped cylinder of pasteboard, this having been an oatmeal box which the maker had abstracted from the kitchen when his wife wasn't looking, and in so doing had left a trail of oatmeal all the way into the living room.

"I'll help you make a set," said my neighbor. "It's easy and a lot of fun. They call this a crystal set, which is the cheapest outfit, but you can hear a good ways with it. After you have played with this a while, you can get something more elaborate. It's the same as the automobile game--you start with a Lizzie and work up towards a Goldbrick Twelve."

"If this radio is a progressive disease I dunno about starting it at all," was my answer. "Another thing, we have quit eating oatmeal our house and that makes me shy a cylinder. Furthermore, if I go into this business, I want to understand it from the ground up, from A to Zed. Now, I'm going down to Washington next week and I'll interview all the scientists and get the inside dope on radio before I make up my mind what to do about it."

Well, I went to Washington. Mr. Hoover's Department of Commerce gave me some documents, including a copy of the United States Radio Laws and Regulations, which among other things prohibit road hogging of the ether, cussing at any wave length or blabbing the secret messages which you and a million other persons may hear. As a matter of fact the laws do not concern the vast majority of radio fans, who just listen in and do not send any messages. The Department of Commerce publishes monthly a Radio Service Bulletin, which is full of interesting official data on the ever-changing and developing wireless situation at all points between Russia, South America and Alaska. The call signal letters of all American broadcasting radiophone stations are given, so that you can tell whether San Diego, Cedar Rapids or New York is talking.

The Etherized Voice

I DIDN'T count up the total number of broadcasting stations. They multiply so fast that last week's tally is out of date. It is enough to know that there are so many stations and they are so well distributed throughout the country that nowhere in the United States are you beyond earshot of the etherized human voice. Let the reader figure for himself what this means to the sportsman, prospector or ranchman who may be a couple of hundred miles from a railroad.

The Department of Agriculture sends out daily all kinds of crop and market news from Washington and from various other stations in coöperation with state authorities. The agriculture people also distribute a number of circulars telling how you can make your own home receiving radio set. A crystal detector outfit as described in Circular No. 120 is estimated to cost $10.70. The biggest item in this total is four dollars for a pair of earphones.

They told me that these circulars were concocted at the radio laboratory of the Bureau of Standards, and that a pamphlet on a new home outfit that was a knockout was being prepared. I hastened to the radio laboratory on the outskirts of the capital. It was a weird place, outside and in. Outside were strung a variety of wire shapes which suggested the effort of a loco inventor to devise an improved system of clothes lines. Inside, among other things, was a toy model of the New York ship channel with twin lighthouses and a ship and a directional radio dingbat, whereby it was demonstrated how the vessel could steer its way through the channel on a dark night without a pilot.

While the man in charge was revolving the dingbat, I heard very distinctly, "Peep! Peep! Peep!" and asked whether chickens were used in the experimental work.

"Those are not chickens," said the man pityingly. "The radio makes that noise for the ship to be steered by. It gets louder or fainter, you notice, according to the position."

There is a narrow line in science between sense and foolishness. Would you believe it that in this laboratory there are a number of little rooms with partitions of mosquito wire and that this wire mesh serves to bar out radio waves that penetrate all kinds of solid substances and travel through the earth itself? It's a fact. You can foil skeeters and the radio vibrations at the same time.

"That new home outfit bulletin that you want," said a young man, "is being held up until we can get permission from a certain patentee to embody a hookup which he claims infringes on his discovery."

"I am told that every other homemade amateur set violates one or more patents, and that there are probably 100,000 such violations throughout the country."

A Twilight of Long New Words

"VERY likely," conceded the young man. "But we feel we must protect patent rights, especially since we are a part of the Government that grants them."

I argued that the patent laws permitted the use of devices for personal experimental purposes.

"Well," said the young man, "I'll go just so far and no farther. You take our Circular LC 48 and our Circular 121. Add to these a quarter of a pound of wire for connectors and you will have a classy regenerative receiver, the kind of outfit described in our held up bulletin."

The young man positively refused to tell me how to twist, tat or crochet that quarter pound of wire so as to make the apparatus work but he said that any radio adept would know how.

The circulars described above are supposedly written for babes and sucklings. But their contents seemed to me rather deep and also subversive of the mechanical principles which I know. Take for example a grid leak. My study of architecture and plumbing has taught me to regard all leaks with abhorrence. But it seems that in radio you must encourage leaks.

Thoroughness is my middle name. What I needed was an elementary textbook that would start me in the subcellar of radio science and take me all the way up to the top floor. A wonderful book published by the Government for this very purpose was recommended to me. It is entitled The Principles Underlying Radio Communication, contains over 600 pages, is neatly bound in buckram and is sold by the Government printing office for the small sum of one dollar. This work is used as a textbook in the Army and the Navy and in schools and colleges.

I felt very grateful to Uncle Sam for practically giving me this wonderful simplified revelation of all the secrets of radio. This was before looking inside the book. I then perceived that it was packed with chunks of wisdom undecipherable to a person of my caliber. It was about as easy to follow as a medical book I once borrowed from our family physician which dilated upon orthopometric therapy of ingrowing warts. Amid the twilight of long new words and of plentiful mathematical formulæ, there emerged a few expressions which sounded as if they could be domesticated. Take the character known as megohm. Why not call it or her Meg for short? We may then be able to recall that Meg is radio queen, being equivalent to 1,000,000 common ordinary ohms who never get their pictures in the Sunday supplement.

Little Henry on a Rampage

AGAIN, take the character who is dubbed microfarad. Let us call him Mike. Thus he becomes almost human. There is finally a most intriguing personality who is called microhenry. It is obvious that this Little Henry of the radio is a small brother to the tin lizzie that rambles on all our highways. When you are listening in for a concert and instead of a concord of sweet sounds, you hear a squawk, blap-blap, rattle and bang, you may fairly surmise that Little Henry is again on a rampage in the air. Perhaps this is not so, but who can tell?

Having culled Meg, Mike and Little Henry out of that remarkable book, I cast it aside.

"Research," I observed to my wife, "is great. But this Henry boy will likely grow up to manhood and his whiskers may even become white before I can apprehend all the abstrusities of this subject. Meanwhile tempus fugit. In five minutes we can purchase for a paltry sum a complete outfit, then erect the antenna and adjust the cat's whisker and by night be listening in to a wealth of news, song and story, saving a world of worry and brain fag."

"Let's," she agreed. "I know you could make a splendid outfit if you cared to spend the time."

I hate soft soap but think that loyalty deserves its reward, so she bought a new hat while I obtained the crystal radio set.

It is superfluous to describe how that set was installed. Also it is safer not to, obviating the criticism of some twelve year-old, "Aw, he did that wrong!" The directions were plain and there was nothing deep about the job. Everything necessary was provided with the outfit. We strung a wire, 100 feet long, between a tall tree and the house eaves. This was the antenna, which coaxes the passing ether waves to tarry awhile. A short insulated wire attached to the house end of the antenna was brought through the wall to a corner of our living room, hooked up to the crystal set and thence led through a hole in the floor to a water pipe as ground.

How Galileo Felt

I LOOKED with misgiving on the insignificant maroon colored contraption placed on a round table in the corner. It was crude and small, less impressive than what my neighbor had devised on the foundation of an oatmeal box. There was a wire-wrapped cylinder as in his fix but mine had a cover. I took off the cover hopefully, expecting to see some real mechanism or mayhap a few Megohms and Little Henrys disporting themselves. But there was absolutely nothing inside. I felt like an Egyptologist who opens a deceased Pharaoh in the hope of finding gold simoleons and is confronted with a bag of spices without market value.

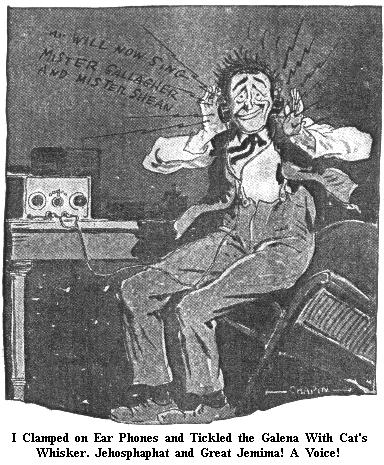

Grimly I clamped on the ear phones and tickled the galena with the silvery coiled wire that is aptly termed cats whisker.

Jehoshaphat and Great Jemima! A voice! As clear and distinct as if somebody was talking ten feet away! The actual distance of this virgin voice happened to be about twelve miles away. I had the sensations of Galileo when he made the world go round the proper way and of Balboa when he added another ocean to the world's supply of salt water.

That cheap little crystal set served us well and faithfully for quite a while. Its ordinary range was limited to something like fifty miles, but once we got a station that was over 200 miles distant. We would have that simple outfit yet were it not for the progressive nature of the malady caused by the radio bacillus. We wanted to have a Big Henry.

The big outfit, which cost round $65, fooled me on size like its predecessor. Instead of being half as large as a piano, the main part of it was contained in a box about eight inches square. There were two modest batteries. The box was very neat and the instrument board looked respectably complicated. There was one vacuum tube which is called a something-tron. My neighbor assisted in the rite of hooking up the new outfit. This was quite simple, since we did not have to change a thing in the antenna or other previous wiring.

We listened most intently for the enlarged music of the spheres.

"The air seems dead," said my neighbor. "Likewise the ether."

We surmised that our something-tron had too many Megohms in its carburetor. A test at the radio shop showed that the tube had paralysis of the occiput. I sent it back to the manufacturer. A few days later a new vacuum tube outfit to replace the defective one arrived. It was cranked up, immediately hit on all cylinders.

What is the practical use of the radio? The same question was asked about the steam engine when it was new. Many farmers find it impractical not to have a radiophone.

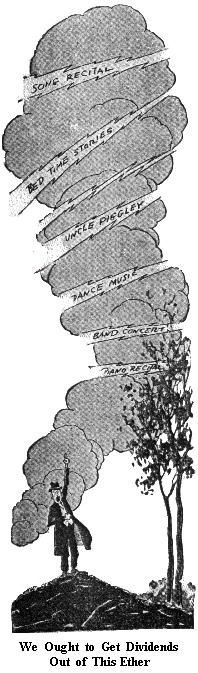

We wanted to go to a concert in the metropolis the other evening. This would have meant railroad fare, admission tickets, several fatiguing hours and much nuisance of dressing up. We stayed at home and yet had a very good concert, in fact we had a choice of two concerts which were being given simultaneously in two different cities.

By moving the pointer of the tuning dial half an inch, we could attend either concert and pick out the selections we liked. When music palled, there was a scientific lecture to be heard one inch to the right.

The telephone is a crude, squawky conveyer of sound compared with the radiophone. You hear a speaker or a singer better at long distance through the ether than if you were present in hall or opera house and heard through the air the same speech song. Wait a moment before you consign me to the Ananias Club. The average hall has poor acoustics, echoes abound and there are also innumerable noises of the audience. At the broadcasting station the entertainer is in a small echoless chamber and there are no extraneous noises.

The radiophone is a marvel. After the automobile, it is to become the foremost agency of civilization. Anybody who feels discouraged about things in general should clamp on a pair of ear phones and tune up.