| Fourth Article. | How Mining Fakes Are Advertised |

"A wonderful architectural structure, a realistic representation of the whole world on a gigantic globe. The interior of this revolving world is entered by thousands of visitors daily, who make the entire grand tour of the world, visiting all countries and all climates, seeing all nations and the inhabitants thereof . . . . most stupendous and overpowering attraction . . . . grand and gorgeous spectacle . . . . ever presented."This "grand, gorgeous, stupendous, overpowering attraction," reduced to cold figures by Pike's "grand, gorgeous, stupendous, overpowering" mathematics, might be visited in a summer by 25,000,000 people. "At twenty-five cents each," figured Pike, "that makes $6,250,000. But let us be conservative. Suppose only 2,500,000 visit our attraction. That would mean $625,000 annually. This would mean that you would receive the first year, and every year thereafter, nearly three times your original investment in dividends alone. These are facts--undeniable facts--which guarantee a brilliant success." Pikes' trip to New York must have been a failure, for he soon closed his office and returned to Hartford. A letter sent to his Broadway office was returned by the post office bearing the stamp, "Not found." Poor Pike! Not found! And only a little while ago you were the "grand, gorgeous, stupendous, overpowering attraction" in the wildcat menagerie!

One feature of the Pike wireless advertising was that there was no promise of dividends. Much of the company advertising of the day was of the guaranteed-dividend variety--Pike, himself, had been the chief exponent of the monthly dividend scheme in his oil promotions. Pike, of course, saw that there was no possibility of earning dividends on his $5,000,000 capital, and that it was impossible to pay unearned dividends without getting caught. Pike made his whole play, therefore, on the similarity between the wireless telegraph and the telephone as an investment; and, instead of promising dividends, he talked only of the marvelous future of the company and the expected rise in the price of the stock. Extravagant as were his page advertisements in every line, still he was clever enough not to tie himself down to many positive predictions. As Sam Keller said, in testifying against his confederates in the Dean swindle, and speaking of Kellogg's get-rich-quick circulars, "no one would 'fall' to them as not being straight, but any one would 'fall' to them by sending along cash." Pike had elaborately furnished offices in the same luxurious office building in Broadway that housed the offices of the Steel Corporation, and there any doubting investor might see the Dolbear instruments at work. The cash flowed into Pike's offices in a steady stream. But the buyers of Pike's stock waited in vain for the opening of the commercial wireless line from New York to Philadelphia. Pike was too busy selling stock to bother about setting up instruments.Bait That Attracted the Fish

"The most marvelous invention of the century."

"Bell Telephone stock, when first offered, went begging at fifty cents a share, and those same shares to-day are worth $4,000."

"Many predict that the stock will soon be selling for as many dollars as cents at the present time."

"More remarkable than the late achievements of wireless telegraphy on the sea is the fact that the Federal Wireless Company has instruments nearing completion for operation between New York and Philadelphia, when it will receive messages at any hour of the day or night, at the rate of ten cents for ten words."

"With the Bell Telephone stock in memory, which went from a few cents to thousands of dollars a share, thoughtful persons are buying up wireless stocks with avidity."

"The career of the company controlling the basic patent in the richest field in America starts with a thousand times more flattering prospects than did the Bell Telephone."

"Stock will soon advance in price by leaps and bounds."

$50 (real money) bought $50 worth of Pike's wireless, January, 1902;Meanwhile, I am in receipt of this appeal from the American De Forest promoters:

= $50 (certificate) watered Consolidated, February, 1902;

= $10 (certificate) unwatered Consolidated, October, 1902;

= $10 (certificate) International, February, 1903;

= $10 (certificate) American De Forest, January, 1904;

= $7.50 (company's money) subscription price of De Forest, St. Louis office, October, 1906;

= $6 (company's money) subscription price of De Forest, New York office, October, 1906;

= $0.85 (real money) cash market value.

"There is not enough stock to go around. Consider the matter carefully. You have the opportunity. Will you grasp it 'at the flood tide' (now) and ride on to the shore of plenty, high and dry above the adversities which often beset old age, to the land of our dreams, where wealth is unbounded and every wish gratified, where comforts admit of enjoyment and wealth admits of opportunities for yourself and those you love? Or will you hesitate and doubt, and let the chance go by, to remain in senile dependency upon the bounty of others? Think! It is for you to decide! Think well! Buy! Do it now!"[The remainder of this article reviewed an extensive list of mining and oil frauds]

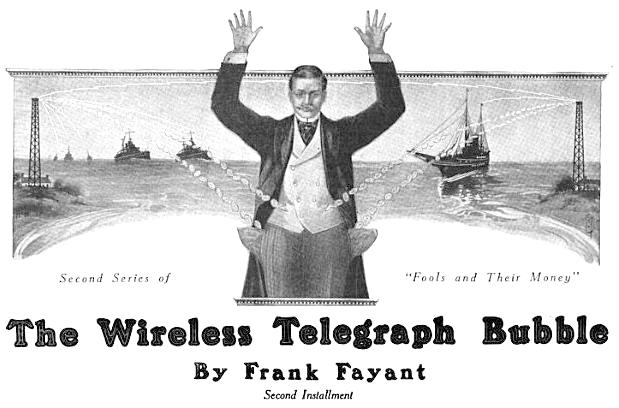

Wireless telegraphy is one of the most remarkable scientific achievements of modern times. That it will forever be of inestimable benefit to mankind is beyond question.

The world owes a great debt to the many men of science in Europe and America who, through years of patient research, have made it possible to send electric messages many miles over the sea, from shore to ship, and from ship to shore.

Nearly all the great ocean steamships that sail from New York are equipped with wireless apparatus, and they are in wireless touch with land stations or with other ships during the greater part of their voyage. With the advance of science, the time will come when every ship that sails the seas will be in daily communication with the land. But the prostitution of this great scientific discovery by parasite promoters with "millions-in-it" schemes of enriching themselves is a story of shame.

Just as a good mine may be a bad investment, as I have shown in the "Fools and Their Money" articles that have gone before, so may a great invention be a bad investment. Wireless telegraphy has been a bad investment. Many millions of dollars of wireless stock have been printed by promoters, and this stock has been sold to investors by flagrantly dishonest methods. Millions of dollars of wireless stock manufactured in the past eight years is to-day worth no more than the paper on which it is printed. Over capitalization, mismanagement, and fraud have wasted millions of money.

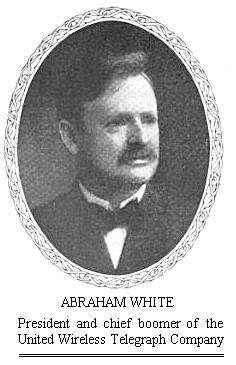

The most shameful chapter in the record of the prostitution of this great invention deals with the network of the De Forest companies promoted by Abraham White, a modern Colonel Sellers. This is the story I will tell in this article and the one that will follow. FRANK FAYANT.

EIGHT years ago this June, when all the world was talking about the remarkable achievement of the Italian boy, Guglielmo Marconi, in sending electric messages without wires, a boy from Iowa took his Ph. D. degree at Yale for special research in the phenomena of the Hertzian waves. His name was Lee De Forest. Marconi was then twenty-four; De Forest was two years older. Only by rigorous economy and self-sacrifice had the young American gained his university education, and, as soon as he won his coveted Ph. D., he went to Chicago to earn a living and a name for himself.

EIGHT years ago this June, when all the world was talking about the remarkable achievement of the Italian boy, Guglielmo Marconi, in sending electric messages without wires, a boy from Iowa took his Ph. D. degree at Yale for special research in the phenomena of the Hertzian waves. His name was Lee De Forest. Marconi was then twenty-four; De Forest was two years older. Only by rigorous economy and self-sacrifice had the young American gained his university education, and, as soon as he won his coveted Ph. D., he went to Chicago to earn a living and a name for himself.

The receiver of the new system is the joint invention of Lee De Forest, a graduate of Yale University, of the class of '96, Sheffield, and Edwin H. Smythe, of the engineering department of the Western Electric Company of Chicago. Mr. Smythe's ten years' work in the field of telephony has given him an experience that has proved especially valuable in dealing with the problem in hand, while, during his three years of graduate work at Yale, Mr. De Forest made a specialty of the subject of Hertzian waves, taking the degree of Ph. D. for work along that line. Readers of the Western Electrician will also be interested in knowing that for a time Mr. De Forest was connected with the editorial staff of this journal, resigning to prosecute work on this invention. The sending apparatus has been developed by Prof. Clarence E. Freeman, E.E., Associate Professor in Electrical Engineering at the Armour Institute of Technology.The three inventors, who had sent messages from the Chicago lake front to a yacht five miles off shore, and who were convinced that, with powerful apparatus, they would be able to transmit signals many times as far, saw the great commercial possibilities of the invention. Young Marconi had already made very successful experiments in wireless telegraphy in England, and was at that time in America continuing his work. Marconi had obtained strong financial backing in England, and was having no trouble in interesting American financiers in the commercial possibilities of wireless telegraphy. The Chicago inventors believed that if Marconi could raise capital they could do the same. So De Forest was sent to New York to raise capital and form a company. De Forest fell in with Henry B. Snyder, a promoter, who immediately saw "millions in it." He assured De Forest that he could raise all the money needed to float a company. He had no funds of his own, as De Forest soon discovered, but he could find some of his friends who would subscribe a few thousand dollars to get the company started. Snyder got five men to subscribe $500 each to the venture. One of these men was John Firth; another was William Newmarch Harte; a third was John Bergessen. When De Forest left his friends in Chicago, the idea had been to name the company the "Freeman-Smythe-De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company," and the three inventors were to be partners in the enterprise. But Snyder thought this name was too cumbersome. He proposed the name "Imperial." A compromise was made on the "Wireless Telegraph Company of America." This company was incorporated in New Jersey, with a nominal capital of $3,000, and the stock was divided among the promoters. This was the nucleus of the present $30,000,000 capital of De Forest companies, with which $25,000,000 of other companies have been merged, and many million dollars more have been planned. The $3,000 company took out the patents on the Freeman "sending apparatus" and the De Forest-Smythe "responders."

"The De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company is incorporated with a capital stock of $3,000,000, divided into 300,000 shares of $10 par value. The company owns the patents of the De Forest system of wireless telegraphy. Under it the American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company ($5,000,000 capital, $10 shares) has been organized as a sub-company, to conduct the commercial work in United States territory. A Canadian company ($2,500,000) has been organized similarly for that territory, and English, Russian, Spanish, and South American companies are in process of organization. In a reasonable time, fifty subsidiary companies throughout the world will be tributary to the parent company. The De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company owns $1,500,000 of the stock of the American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company. The revenue of the company will consist of dividends on holdings in the subsidiary companies, yearly royalties on the patents, and profits on the sale of the wireless apparatus."A publicity campaign worthy of "Tody" Hamilton was engineered by White. He spared no effort and no expense to keep the newspapers talking about the De Forest system. The De Forest instruments did their work, and did it well, as was shown in the competitive tests with the Marconi instruments, when the Navy Department bought De Forest apparatus in preference to the Marconi. [See correction] White immediately heralded this news broadcast, and advertised the De Forest system as "the system adopted by the United States Government." The Marconi people, seeing that White was getting the best of them, brought suit for infringement of patents. For technical reasons, the Marconi people could not get a permanent injunction until three years later, and by that time the De Forest companies had devised apparatus more efficient than that brought on from Chicago by De Forest. White hired a press agent, and it was on the suggestion of the press agent that a suit for $1,000,000 damages was brought against the Marconi company. The suit was only brought to give the newspapers something to talk about. It was soon forgotten. The De Forest prospectuses, written under the direction of the imaginative White, were wonders to behold. Here is a table of estimated yearly earnings for the $3,000,000 De Forest Wireless:

"Commercial wireless telegraphy, at a rate of one cent a word to the general public from Chicago to all principal points in the United States, will be an assured fact within ninety days, if the plans of the American De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company are carried out. Within sixty days it will be possible to flash messages from Chicago to steamers on the lakes, and to Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, New York, and the Atlantic seaboard. Almost as soon, we will be in wireless communication with St. Louis, Omaha, Kansas City, and Fort Worth. A statement that these things would be accomplished was given out yesterday at the Chicago office of the company by Abraham White, president of the corporation, and Dr. Lee De Forest, whose inventions are claimed to have been made before those of Signor Marconi."Then followed a characteristic Colonel Sellers interview with White, detailing the plans he had for installing the De Forest system all over the face of the earth. The one-cent-a-word rate would go into effect in New York within a few days, and would extend to other parts of the country as fast as the system was installed. Following the Chicago "Inter-Ocean" article was this bit of verse:

A little bird sat on a telegraph wire,

And said to his mate, "I declare!

If wireless telegraphy comes into vogue,

We'll all have to sit on the air."

$100 put into this stock now for children will make them independently rich on reaching their majority.At that time White was selling the preferred stock at $10 a share, with an equal bonus of common stock. He also had a "special treasury" plan for selling this stock at $15 a share, with a "2-½ per cent. monthly distribution." Investors who could n't buy all of this stock they wanted for cash were allowed to buy it on the installment plan--$2 down and $2 a month. It was the "greatest opportunity of the twentieth century for enormous profits." The $15,000,000 company was only a few months old, when White wanted to print more stock. He announced in the newspapers that he was forming the Amalgamated Wireless Securities Company, capital $10,000,000. The scheme of the Amalgamated was "to relieve the American Company from the expense of extending its work in foreign parts, and, at the same time, contribute large amounts of money for its home work." Some of White's fellow promoters could n't see why he wanted to print $10,000,000 more stock immediately after organizing the $15,000,000 company, and they entered so vigorous a protest that White gave up his Amalgamated idea.

Stock in the De Forest company is as good a buy now as telephone stocks were in 1877 and 1878, and those who buy now for holding will receive returns little less than marvelous.

Just as soon as the company is on a dividend basis, the common stock with the preferred should advance to figures practically without limit. This is a stock that should be purchased in just as large quantities as an investor can afford. If set aside for two years, it is morally certain to be in demand at 1000 per cent. or more over present prices.

Tremendous developments are under way.

A few hundred dollars invested now will make you independent for life.

We desire to say to you that you are making a fool of yourself, as the stock you now hold is absolutely worthless, but we have given you the opportunity to make the exchange, and under no circumstances now will we accept your shares after the various letters we have received from you. We desire to say to you that, for the purpose of protecting shareholders of the Dominion De Forest Company, we have personally advanced over $50,000 to that company for the purpose of paying bills, etc., and we have stood between the company and its creditors for the benefit of its shareholders for just about as long as we desire. Now, you claim that you have certain certificates that bear interest. Possibly you have, and possibly you have not. The shares we represent are absolutely bona fide, and are not schemes to defraud, and we wish to inform you that the money you will lose in this transaction will be brought about by yourself, and you have no one to blame but yourself.The new company, the shares of which Mr. Humphrey wished to sell the Rochester investor instead of sending him his interest checks, is the Northern Commercial Telegraph Company, Ltd., with a capital of £750,000 ($3,750,000). The officers of this company are Lieutenant Colonel Sir Henry M. Pellatt, of Toronto, chairman; E. W. Humphrey, of Montreal, president; F. Orr Lewis, of Montreal, first vice president; S. H. Ewing, of Montreal, second vice president; D. M. Stewart, of Montreal, treasurer, S. Carsley and Charles Morton, of Montreal, and Lieutenant Colonel Robert Cartwright, of Ottawa, are also directors. From the "confidential preliminary prospectus" of the Northern Commercial Company, I learn that the company proposes to own 200,000 shares of the 240,000 shares of the Dominion De Forest Wireless Telegraph Company, Ltd., and 110,000 shares of the 150,000 shares of the Canadian Radio Telegraph Company, Ltd. The Canadian Radio is an offshoot of an English company, of which Lord Armstrong is the head, and which owns the wireless patents of Daldemar Poulsen. The Northern Commercial, in addition to sending Poulsen messages across the Atlantic, and De Forest messages up and down the Great Lakes, also intends to use the old-fashioned wire method to send telegraph and telephone messages to the uttermost parts of Canada. The Northern Commercial mathematician, although not as proficient in the art as White, does pretty well. Adding up all the various sources of revenue from wire and wireless services on the ocean, the lakes, and the land, the Canadian mathematical shark figures out that the Northern Commercial will earn forty per cent. on its capital.

"The board of directors is headed by the Right Hon. Lord Armstrong, world-famous shipbuilder, and associated with him are Arthur M. Grenfell, of the firm of Chaplin, Milne, and Grenfell, bankers, J. Nevil Maskelyne, and --- Fras, inventor and electrical expert. The English Government has granted a license for the erection of De Forest stations in the British Isles, including a transatlantic station. In addition to commercial stations, orders have been received from the British Government for eleven stations, including three in India."It was announced, a short time ago, that the English syndicate had "closed a contract to pay £160,000 ($800,000) for the patents of the world, except the United States, of the Poulsen system, and that it agrees to find an additional £100,000 ($500,000) as working capital."

ABRAHAM WHITE, the chief promoter of the De Forest companies, is a stock market plunger. More than once he has run a shoestring into a fortune. Last August, when Mr. Harriman startled Wall Street by putting Southern Pacific on a five per cent. dividend basis, and raising the Union Pacific rate from six to ten per cent., White was plunging on the bull side of the market in a Broadway brokerage house. He began buying Union Pacific at $140, and "pyramided" as the price advanced. The night before the announcement of the Harriman dividends, when Union Pacific was selling around $161, White was long of a big line of the stock, the most of it bought on his paper profits. The next day Union Pacific soared to $177, and not many days later it was selling at $195. In the parlance of the Street, White made a "killing." He says that he made $2,000,000, but $200,000 would probably be nearer the real figure. He made enough money, at any rate, to put him on Easy Street for a while and to start him building more air castles. One of these air castles became a reality. White heard that the famous John A. McCall country mansion at Long Branch, N. J., could be bought at a bargain. He drew down a big share of his Union Pacific profits and bought the magnificent country seat. Here is White's own authorized version of that deal:The President of the De Forest Company and His Extraordinary Career--One Air Castle That Became a Magnificent Reality--The Daring Financial Schemes Planned Within Its Walls--How Wireless Stock Trading Was Finally Made a Monumental Farce

"Hardly had Wall Street recovered from the news of his great success in gathering in about $2,000,000 in an afternoon, before Mr. White had unwittingly stepped into the limelight again. He purchased the magnificent mansion erected at Long Branch for the late John A. McCall, when he was president of the New York Life Insurance Company. This great palace, which presents a most attractive and harmonious assemblage of lines from whatever point it is viewed, is said to have cost, including its furnishings, about $830,000. What Mr. White paid for it is not known. 'Something under $500,000,' was the announcement made after the sale.

The Purchase of the McCall House

"Again Mr. White's luck was with him. Other wealthy and sagacious men had become elevated to the millionaire ranks the same afternoon the ticker raised him among plutocrats. They, too, had had their eyes on the McCall house, waiting only for a lucky stroke in the market to enable them to make the purchase. But Mr. White, as usual, was early on the ground. On Sunday, week before, he and Mrs. White drove to Long Branch and inspected the great pile and its fifty-eight acres of elegant grounds, its own fire department, etc., and were pleasantly impressed with the place. So, when fortune was within his grasp, he closed the bargain for the place at once.

"Then the telephone bell in his office began to give him trouble. The other new millionaires who were ready to buy the Long Branch palace discovered they had been forestalled. But they were generous. How much would Mr. White take for his bargain? They offered $10,000, $20,000, even $50,000 bonus within an hour after he had made the purchase. He advised his secretary: 'I won't sell. Tell them $100,000 bonus will not do; if you think they are willing to give that, tell them $200,000 more will not do. I will not sell.'

Made the Ticker Pay the Bills

"In going through the house the previous Sunday, Mrs. White was particularly fascinated with the magnificent music room. She is considered a fine musician, and is the possessor of an exquisite voice. 'Cora,' remarked Mr. White to his wife jokingly, 'how would you like to have this room to sing in?' She replied that she would be charmed with it. 'Well,' added her husband, 'if my Union Pacific deal comes out all right, I will buy the place for you.' So he bought the immense house, furnishings complete. Yet, when Mrs. White went to it as its mistress, she discovered that some things were needed, especially silverware, china, and linen. About $5,000 would be needed for the purchases.

"Mr. White concluded to feel the pulse of the tape again. He had $5,000, certainly--many times $5,000--but he has faith in being able to make the ticker pay his bills. So he went to his brokers, He looked at the tape a few minutes. Great Northern preferred came on the ticker at 305. Remarking, 'That looks cheap,' he turned to the managing clerk, who remarked he had three hundred shares at that figure. 'I'll take you; and buy me two hundred more at the same price and get me five hundred Northern Pacific at $210 or better.' He continued to buy until he had five hundred of Northern Pacific and five hundred shares of Great Northern preferred. The next day Mrs. White called at his office ready to go out shopping. Mr. White asked her to wait a few minutes until he went to his brokers. There he closed out his shares in a few minutes at a profit of $12,500."

"He lunched with a member of the brokers' firms with which he had been dealing, and, as he could keep in close touch with the ticker at the same time, he laughingly exclaimed to his host, 'Billy, I 'll give you an order to buy something every minute we are at the table.' He really was joking, but he actually did it. At the end of the meal, which had lasted fifty-eight minutes, he had bought an aggregate of 58,000 shares of various stocks--Union Pacific, Southern Pacific, Amalgamated Copper and Pennsylvania among others. His speculations carried on during his luncheon had netted him a profit of about $25,000. Is it any wonder he subsequently remarked he had had a pleasant luncheon?"White installed himself amid the luxurious surroundings of the famous McCall mansion, and it at once became the rendezvous for "millions-in-it" dreamers. Men with lean pocketbooks and fat imaginations, picked up by White in the highways and byways of the metropolis, spent week-ends at "White Park" and dreamed of $100,000,000 companies that were to spring up in the great marts of the world. Ambitious but unknown inventors, scientists, attorneys, speculators, miners, and near-capitalists gathered nightly in the great foyer hall of the McCall mansion, sipped their host's good wines and dreamed great dreams. It was at one of these Arabian Nights' entertainments that White conceived the idea of merging all the wireless telegraph companies in the world in one grand, glorious, glittering aggregation. The De Forest and Marconi companies had been engaged for years in costly patent litigation, and each promoting crowd had been calling the other names, and claiming that it had the only simon pure wireless telegraph monopoly. The idea looked so big to White, that, without making any overtures to the "enemy" (the Marconi people), he announced in the newspapers one Sunday morning in November the formation of the United Wireless Telegraph Company, capital $20,000,000, "organized for the purpose of uniting the American and foreign systems of wireless telegraphy, including the Marconi and American De Forest systems, as well as acquiring the latest and most approved methods and inventions employed in the art of wireless telegraphy, and continuing its development and expansion throughout the world on the broad and comprehensive scale which the enterprise merits."

While I was thinking over this golden opportunity, I received a letter from the New York office of the company offering the same stock for $6 a share. Meanwhile, I was, in receipt of offers from various brokers to sell me the stock for 90 cents, 85 cents, and 80 cents a share. I again wrote to the New York office asking why there was a difference of $1.50 between the company quotations in New York and St. Louis. A telegram came back stating that $6 was the only official price for the stock. A day or two later I received a letter from the Greater New York Security Company, stating that the New York office had no authority to offer the stock at less than $7.50. I then timidly asked for an answer to the riddle of the 80 cent stock offered by brokers. "We have never paid any attention to what the enemy or the cut-rate brokers may do with the few shares they may obtain from weak stockholders," the company answered. "We have received a great many complaining letters from persons who have invested their money with brokers and afterwards have been unable to obtain delivery of the certificates, and it is a source of deep regret to us that some people have suffered a loss in this way, and we wish to warn you in time."Prices to Suit All Purses

"Consider the matter carefully. You have the opportunity. Will you grasp it at the flood tide (now) and ride on to the shore of plenty, high and dry above the adversities which often beset old age, to the land of our dreams, where wealth is unbounded and every wish gratified, where comfort admits of enjoyment, and wealth admits of opportunities for yourself and those you love? Or will you hesitate and doubt, and let the chance go by, to remain in senile dependency upon the bounty of others? Think! It is for you to decide. Think well! Buy! Do it now!"

"The stock is selling readily, and men of ability can easily earn from one hundred dollars to five hundred dollars a week. This is a rare opportunity to become identified with an enterprise that will reflect both credit and profit upon all who are connected with it. The company is now earning money every day and every hour, and is a greater monopoly than the Bell Telephone."In order to cover up the sins of the past, the United Wireless promoters have evolved a fearful and wonderful plan of exchange of stock. In the whole history of finance I have been unable to discover anything like it. Our American code of financial morals has recently been under rigorous investigation, and some doubtful practices have been uncovered, but never before, to my knowledge, have the promoters of a $15,000,000 company attempted arbitrarily to fix various values for the same stock. The financial management of the Union Pacific Railroad has recently been severely censured, but the searching investigation of the Government has failed to show in the minutest particular that one share of Union Pacific was not as valuable as any other share, no matter when nor where bought, nor at what price.

"For every dollar paid by you for De Forest preferred or common stock, there will be issued $1.10 worth of United Wireless Telegraph Company's preferred stock, plus 5 per cent. thereon for every year the stock has been held by you for over one year. To the holders of bonds who desire to exchange for preferred stock, we will exchange by allowing 20 per cent. on the par value of the bonds, and the holder will be allowed to retain his bonus stock. To the holders of bonus, cut rate, or brokers' stock, we will exchange at the rate of one share of United for six of American De Forest. This applies to either preferred or common stock purchased prior to January 1, 1907. All stock exchanged must be held in escrow in bank or trust company for two years."As the De Forest stock is intrinsically almost worthless to-day, it probably matters little to its holders on what basis they exchange it for more wireless stock. The stock that the promoters were selling last year, with the alluring promise that it would return hundreds and thousands of per cent. a year dividends, can now be exchanged for a new stock that the promoters themselves are not very certain will return any dividends at all. The bondholders are in a sorry plight. They had a first lean on the assets of the American De Forest Company. Now they have an opportunity to exchange their bonds at a discount of eighty per cent., for part of a $10,000,000 stock issue. These bonds, the total issue of which was $500,000, were brought out late in 1904, when the company was sadly in need of funds, and could not raise any more money by the sale of stock. The bonds were brought out in a peculiar manner. White, as president of the American De Forest, executed a trust deed to White as president of the Greater New York Security Company. About $270,000 of these bonds were sold, many of them going to investors in the West, and the remainder to American De Forest stockholders in New York, Atlanta, and other Eastern cities. They bear interest at the rate of six per cent. The quarterly coupons were honored until last December. Since then the interest on the bonds had not been paid. The bondholders, if they have any faith in the future of their company, can exercise their rights as creditors of the company and put it in the hands of a receiver. They certainly ought to have as good a chance of getting a run for their money this way as they will have by selling their bonds for United Wireless stock at a discount of eighty per cent.

"The following wireless circuits have been opened for business--Chicago and Springfield, Springfield and St. Louis, St. Louis and Kansas City, and Buffalo and Cleveland; apparatus is now being made ready for a complete line of stations connecting New York and San Francisco, and we are informed that wireless communications between these two points will be established within the next eight months."This was also a dream. Only last November, when White was still counting the big profits of his lucky speculation in the stock market, he was "planning to effect instantaneous communication from the Pacific Coast to China in the near future." This was another dream.

Dear Sir:--I have read your admirable article published in SUCCESS MAGAZINE for June, and to only one matter would I take exception, viz.: that you state "the De Forest instruments did their work and did it well, as was shown in the competitive tests with the Marconi instruments." This company entered into no competitive work whatsoever and it does not approve of such tests. In lieu thereof we offered to show the Government our actual working on a commercial basis. As the above statement is rather misleading, if you can correct it I shall feel much obliged. Yours very truly,

|

| * * |

| A Correction |

| In the June issue of Success Magazine, Frank Fayant, in his article, "The Wireless Telegraph Bubble," spoke of the "Western Electrician" as "the journal of the Western Electric Company." W. A. Kreidler, the president of the "Western Electrician," writes us to deny this statement. An inadvertent injustice having been done him and his paper, we take pleasure in retracting the statement. |

| * * |

| It Drove Him Out |

| Deming, N. M., June 28, 1907. |

| Editor, SUCCESS MAGAZINE,

Dear Sir:--The June Number, with Mr. Fayant's article, "The Wireless Telegraph Bubble," reached Deming most opportunely. The gentleman whose card is inclosed had been in town for several days in behalf of his company. He had sowed a good deal of seed, and, confident of a good crop, left for Silver City to plant another crop. In the meanwhile, Success Magazine arrived. The copies were eagerly read. The gentleman returned, but the harvest could not have been up to expectations, for he did not tarry long. The mention of SUCCESS MAGAZINE was enough to cause him to shut off the hot air, fold up his books and pamphlets, and, like the Arabs, silently steal away. |

| H. D. G. |

| A Correction |

| THE following communication, signed by Mr. C. C. Wilson, president, and Mr. S. S. Bogart, treasurer, of the United Wireless Telegraph Company, of 42 Broadway, New York City, we gladly give space to here. It will set aright any wrong impression that may have been given in Mr. Frank Fayant's articles entitled, "The Wireless Telegraph Bubble."

Editor, Success Magazine, Sir:-- In the June and July numbers of the Success Magazine, articles appeared on wireless telegraphy written, as we understand, by Mr. Frank Fayant. In both articles he refers to the Atlantic DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company as a subsidiary to the American DeForest, and as the only part of the DeForest System that was producing a revenue and that said subsidiary company was owned and controlled by Mr. Abraham White. Mr. Fayant was advised that this statement was incorrect and misleading and was damaging to the United Wireless Telegraph Company, as that Company owned and operated the so-called Atlantic DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company as the Marine Department of the United Wireless Telegraph Company, having in its treasury 99,883 shares out of a capitalization of 100,000 shares. The remaining shares are owned by Directors and the Treasurer of the Atlantic DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company. Mr. White at no time owned over five shares of the stock of said Company. We believe injustice to us that this statement should be given prominence in your Magazine, to relieve the erroneous impression created by the articles above referred to. |

| Yours very truly, |

| UNITED WIRELESS TELEGRAPH COMPANY. |