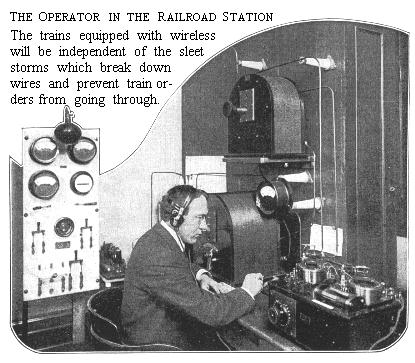

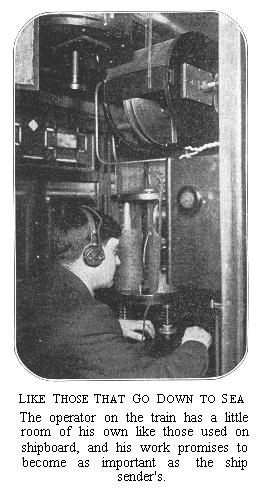

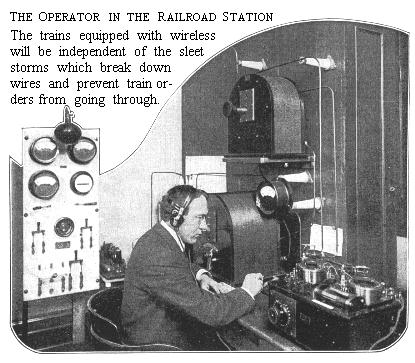

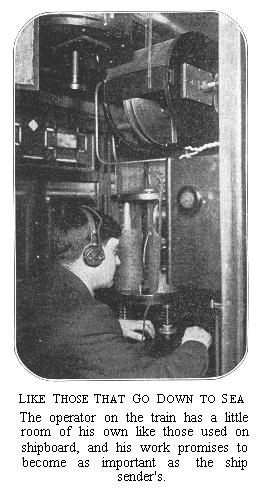

Technical World Magazine, February, 1914, pages 914-918:

GETTING the WIRELESS on BOARD TRAIN

By Charles Frederick Carter

WHEN Frederick Wally stepped out of a little cubby-hole in one corner of the forward day coach on the Lackawanna Limited, west-bound, as it neared North Scranton, Pennsylvania, Tuesday, November 25, 1913, and pinned a sheet of paper on the wall, the passengers in the front seats, who had been casually wondering what caused the strange, crackling sounds that had been coming from the cubby-hole, pricked up their ears, figuratively speaking. Some of the more curious left their seats to see what the sheet of paper might be. With uncomprehending minds, they read these words in the peculiar round hand affected by all telegraph operators:

"After a lull of a few hours the battle of Tierra Blanca was resumed this morning. General Villa, commanding the rebels, ordered the artillery turned on a Federal train his troops had surrounded during the night. The battle is now extending along a front of twenty miles."

One of the passengers peeked into the cubby-hole, then exclaimed in tones of amazement:

"Wireless, by jinks!"

Then the amazed traveler rushed back through the length of the train, spreading the incredible information that a wireless operator was on board receiving news bulletins just as was done on ocean liners.

In a little less than no time five coach loads of passengers were trying to crowd into the front end of one car. As Operator Wally pinned up bulletin after bulletin the passengers began to realize that they were witnessing a historic event; for those news bulletins were the first ever received by wireless telegraph on board a moving train. To be more specific about the moving, it may be said that the train was running somewhere between fifty and sixty miles an hour, for it is the fastest on the road.

Altogether some two hundred and fifty words of condensed news bulletins were received. They were read over and over until most of the passengers could have repeated them and nothing but this latest and most wonderful development of the wireless telegraph was talked about on the Limited that day.

Thirty miles east of Buffalo, Wally, who did not know the call for the wireless station at that city, began calling for "radio station". The operator at the wireless station maintained by an evening newspaper happened to be staying late that night in order to deliver a message to a steamship somewhere on Lake Erie. Thinking he had picked up the steamer, he answered, and to his inquiry Wally replied:

"Lackawanna Limited. We've got a wireless outfit on board."

"Quit your kidding," retorted the newspaper man.

"Not kidding. Come down to the station when we get in and see."

The incredulous wireless operator, who acted as if he knew he was being victimized but was resolved to see it through, was waiting when the Limited pulled into Buffalo. He could hardly be convinced even when Wally proudly exhibited his train outfit. Four days later the first commercial message ever handled by wireless telegraph from a moving train was sent by a traveling salesman.

Preparation for the experiments which led up to these results were begun by the Delaware, Lackawanna and Western Railroad last summer in the hope of developing a more reliable method of directing the movements of trains than is now available. In response to a somewhat insistent public demand, twenty-five other railroads had for some time past been industriously experimenting with automatic train stops. Results attained by these roads were so discouraging that the Lackawanna started out on a new line by instructing the general superintendent of telegraph and telephones to see what he could do with wireless. Sandwiching this new task in between their regular duties, the Lackawanna's own linemen erected towers at Scranton, Pennsylvania, and Binghamton, New York, sixty-two miles west. The towers complete cost three thousand dollars each, and eight hundred dollars was paid for one train outfit.

The experiment was begun merely with the idea of ascertaining if the wireless was not more reliable than the usual form of telegraph. Sleet storms, particularly in the mountains, often break down the wires, thus paralyzing traffic. It will be remembered that when President Taft was inaugurated every wire leading into Washington was broken down by a sleet storm. As a result not a train could be moved in or out of the capital for some hours.

The towers were ready for service November 4. On that date the first train order ever sent by wireless telegraph was sent from the dispatcher's office at Scranton to Binghamton, where it was duly delivered to one of the train crews in the regular way. It was hardly surprising to find this test was a success, for the wireless telegraph has been in operation too long to leave any doubt on that score. What remains to be determined is whether thunderstorms, or any other disturbance of the elements, will interfere in any way. Train orders, unlike commercial messages, do not admit of delay.

The attempt to communicate with moving trains was an afterthought, but an important one. Statistics show that three-fourths of train accidents are due to forgetfulness or negligence by employes. The demand for automatic train stops is due to the realization of the necessity for some means of preventing accidents when the human element fails. If the dispatcher could keep in continual communication with trains, he could call attention to orders that had been overlooked or misunderstood in time to prevent disasters. But this is by no means the only reason why continual communication with trains on the road is desirable.

Through freight on the Lackawanna is moved in trains of eighty to ninety cars drawn by two or three engines, and on the heavy grades near Scranton by four, or even five, engines. There is no occasion for these heavy trains to stop except for orders or to allow a passenger train to pass them. The company is averse to having these trains stop oftener than is necessary, because it costs from ten to fifteen dollars to stop and start again. Besides, in about four stops in ten with these long trains a drawbar or two is pulled out in trying to get under way. Every drawbar pulled out costs from forty to fifty dollars, aside from the delay and interruption of service. It may readily be seen, therefore, how important it is to the railroad to keep its trains moving.

One way to accomplish this is to cut out stops for orders, which could be done if the wireless telegraph could be made to work between the dispatcher's office and the caboose.

The wireless telegraph would prove equally useful in delivering orders for passenger trains; it would be serviceable in sending news bulletins for the edification of passengers and also enable them to send messages without waiting for the train to stop at a telegraph station.

The wireless telegraph for use at sea and for long-distance transmission has been well developed. But before it could be applied to the railroad a good many problems had to be solved. In the first place, a wireless station must have a ground wire just the same as the ordinary form of telegraph. A moving train obviously could not have a ground wire, but could it use the rails instead? Again, the Lackawanna is equipped with automatic block signals, which use the rails for a part of the circuit. Would the use of the rails for a ground wire for the wireless telegraph apparatus on board trains interfere with the working of the block signals? If so, then the wireless would have to be abandoned, for the block signals cannot be dispensed with.

Still another problem was the electric current required to operate it. The only source of supply was the train lighting system, power for which was obtained from the car axles. Would this current prove satisfactory? If it did, would the wireless use enough of the current to dim the lights? If it did, then that settled the problem.

The first train equipped with wireless telegraph left Hoboken for Buffalo, November 21. On board were the general superintendent of telegraph and telephones, a Marconi operator and several Marconi experts. All uncertainties quickly vanished. When thirty miles east of Scranton the train raised the wireless station there without difficulty. The rails proved entirely satisfactory as a ground wire; block signals were not interfered with and the train lighting current served admirably for the wireless without perceptibly affecting the lights.

There were, of course, other difficulties. The noise of the train was confusing, but the operator found that he could get used to it just as an operator grows accustomed to the din of a big telegraph office, though it is very distracting at first. Again, it was found that in going around curves the sounds grew fainter. This trouble, also, proved to be less serious than was apprehended. In short, the fact soon developed that the wireless telegraph was as well adapted to communication with moving trains as with moving vessels at sea.

The apparatus used being much less powerful than that used on ships, its radius of communication is smaller. On that first day, the train was in continuous communication with one of the two stations from a point thirty miles east of Scranton to a point thirty miles west of Binghamton. This radius has been increased as experiments have progressed.

On the second trip the wireless demonstrated its practical usefulness. First, the conductor became ill. Ordinarily, a delay in getting a substitute would have been necessary. Either the Limited, which makes few stops, would have had to make a special stop to allow a telegram to be sent, or it would have had to wait at Scranton while the substitute was secured. In this instance, a wireless message was sent while the train was running at its usual speed. The substitute was waiting on the platform, grip in hand, when the train pulled into Scranton. Besides this, the train was so crowded that the conductor saw he would need another coach. The wireless operator asked for the coach while the train was running; and a switch engine was waiting with the car all ready for a quick coupling when the train reached Scranton.